So I was delighted to happen across a bottle while playing hooky from a conference this weekend in Washington DC. I brought the bottle home with me. It took something of a miracle not to have drunk it on the spot.

Incidentally, I also had great sushi while in DC. But more on that some other time.

Banyuls, in addition to being a delicious dessert wine, is also a geographical region. That's the whole point of the "AOC" denomination, of course: the French appellation d'origine controllée (like the Italian Denominazione di origine controllata, the Spanish Denominación de Origen, and so forth) demarcates regionally-specific products whose standards of quality are protected by a national institution. This is not, however, simply a administrative organ for maintaining quality control, such as the USDA. For it is also a system of regional support and specialization. Thus, for instance, if you want to find out more about the Banyuls region, you can go to the Banyuls web site: www.banyuls.com

Short of exercising some misty-eyed Europhilia, I wonder if there's a way to develop a system like this in the US. To a certain extent it already exists. There are, for instance, a number of US wine regions, as legislated by some tax-based department of tobacco and alcohol. But the very fact that this bureaucracy derives from taxation already makes me suspicious. Especially given the lingering traces of the Prohibition movement in the way states determine their blue laws. What about a broader sense of regionalism, devoted as much to food as to wine?

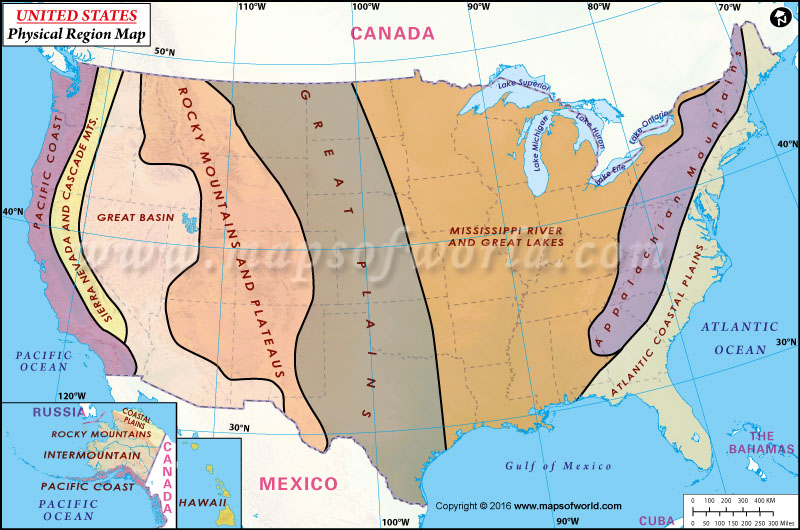

Let's side-step the problem of administration for the moment. It strikes me that a system for regional specificity in the US would first have to come up with a sense of how the country breaks down on regional lines. No easy task. Where would we start? Would the regions be derived from the products, or the products from the regions?

For one, not every region bears the same set of products. New England clam chowder has a cream base. Manhattan clam chowder has a tomato base. Rhode Island clam chowder (also native to parts of Connecticut) has a clear broth base. Aha! A regionalism! Indeed, there is no Minnesota clam chowder, since they don't have clams. San Francisco has clams, but do they don't have a native chowder.

Alternatively, some artisinal products are themselves regionally specific: scrapple, as far as I know, is limited to the Amish and Mennonite regions of central Pennsylvania and Ohio. Steam beer is a San Francisco product.

What might a regional map of the US look like? Cruising around the internet yields numerous attempts to derive some sort of overall coherence, from the silly—

— to the drily bureaucratic

But does a region have to conform to the outlines of a state? According to the Alcohol and Tax and Trade Bureau web site, an appellation of origin can be as small as three counties (although it then becomes a "multi-county" appellation). Lines of political demarcation might have something to do with US regionalism-- the Mason-Dixon line comes to mind here-- but I can't imagine that they're so significant as to determine the contours of every region.

Another possibility might be to use the USDA climate-zone map

as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.

as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.We're not raised to think this way. Think of your grade-school social science classes: it's all based on economics and raw materials, not on artisanal products made with these raw materials. Idaho= potato. California and Florida= oranges. But what do local folks make with them?

I'll come back to this idea from time to time, as it's both a concern and an interest of mine. I also welcome any thoughts.

No comments:

Post a Comment