Whether or not you've read anything by that Proust fellow, you're aware, no doubt, of the idea that Madeleines have a special place in the way we think about food.

This is a bit like saying that the Great War brought about, you know, a few changes in European life.

All the same, it may be worth dwelling on the question of how food induces us to remember moments from the past, whether voluntarily or involuntarily.

It wasn't just Proust who was thinking about this around the turn of the century. The slightly elder Huysmans pondered, in fictional terms, the possibility of synthesizing experience altogether. His protagonist, des Esseintes, lives amongst a battery of perfumes and dyes, forging experience from bottles, pill-boxes, and alembics. Imagine Hemingway with his cabinet of empty bottles, but without the war.

Taste, smell, and the disorder of the senses: herein lies the true fabric of our experience. Do you buy it? This is all fine in theory, as well as in the literary practice of the late 19th century. But how does it work in terms of our own contemporary reality? Does food really invoke memory with the sharpness and clarity we often wish to ascribe to it?

I know my friend Emily Z. would have something to say about this, and I hope that she will. As for me, I admit upon reflection that I've been overtaken by a nagging suspicion: to what extent are many of our food memories discursive rather than sensory? If I harbor strong feelings for my uncle's jellied beef tongue, or for my mother's savory cheese pies, is this on account of the food itself? Or does it have to do instead with the exchange of ideas and excitement that surrounds them? I'm beginning to think that it has as much to do with the talk, as with the taste. Sacrilege?

But I ask you: when someone passes down a recipe, do we recall the taste of the dish, or the bounty of knowledge the recipe supplies?

I'm thinking of the time I learned to make blue (sorry: bleu) cheese dressing at Tonya's Restaurant. It was a filthy experience, yet no less gripping for its powerful inspiration of revulsion. I can't quite recall the exact scale of the operation, but it was huge: let's say we mixed the dressing in a 20 gallon bucket. It was white and monstrous-- the bucket, that is-- with gradations embossed on the side. Into this bucket we emptied a 5-pound bag of crumbled blue (sorry: bleu) cheese, followed by a 2-gallon jug of mayonnaise, a 2- gallon jug of sour cream, and-- now things grow slightly more vague-- perhaps a gallon jug of white vinegar. Then we stirred the whole thing. Slopping it all around until it all the pockets of blue (sorry: bleu) cheese were more or less evenly distributed.

There's something very powerful about this memory. More than just the sense of disgust with which I remember the sound of the mixture turning over as I mixed it, lugubrious and unguent, I recall the novelty of the recipe's absurdist scale. I did taste the dressing at one point, and it was piquant and vinegary, in spite of its obscene fat content. But more than anything I remember the sense of initiation with which I undertook the whole operation. This may have been a standard blue (sorry: bleu) cheese dressing, yet making it in a restaurant meant that you made it in bulk rather than purchasing it ready-made. This saved money, I guess. Most of all, the enormous scale of the venture was its most impressive element: one week's worth of dressing was more than a single person could, I presume, humanly tolerate in a lifetime of weeks.

This sense of scale, perhaps more than anything else, is what impresses me about Stanley Kubrick's film of The Shining. The immensity of the kitchen in the Overlook Hotel, as well as of the corresponding exhaustion of forging a simple meal for three from its enormity, is overwhelming. Here lies the true sublimity of the film: how do you find a way to cook for three people (one of whom is utterly, murderously, bat-shit crazy) from 100-pound blocks of frozen ground beef?

This isn't the stuff of memory. This is the stuff of nightmare.

To what extent does eating enter the nightmare? Do we ever really remember food?

Monday, March 31, 2008

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Chicken in a Pot

It's mid-afternoon, and outside the weather is sunny and crisp. It doesn't quite feel like spring just yet. But it's close: it feels as if spring has sent along its representatives, who have come to survey the scene. This is fine with me. They're getting things ready.

As I sit here with A., with whom I took a brisk constitutional earlier this afternoon, I find my thoughts wandering toward the question of dinner. What to eat tonight. Something to reflect the mood of the season, the mood of the day: not quite spring, but hardly winter.

Like the hardy first shoots of the tulips and daffodils bursting from the ground, a vision appears. I see a chicken. And it's in a pot. The broth is light: delicate and pale in color. There are some vegetables around it.

This should not resemble coq au vin, with its November hues and warmth-inducing richness. Today's chicken— as I now realize— must be a spring chicken. Subtle and light, and fragrant with fresh herbs. It is to be a fulfilled wish: we lift the lid to find brightness and light. The promise of spring.

(To be continued...)

*** A Pornographic Interlude****

It's surely a sign of spring, too, when everyone starts shopping again. This photograph arrives courtesy of Mikey B., who enclosed it in an email this evening. The picture depicts a slab of pancetta, as well as the knife that will shortly render it comestible. The photo, he writes, was (I quote):

It's surely a sign of spring, too, when everyone starts shopping again. This photograph arrives courtesy of Mikey B., who enclosed it in an email this evening. The picture depicts a slab of pancetta, as well as the knife that will shortly render it comestible. The photo, he writes, was (I quote):

...taken shortly before it was cubed & fried up for a linguine/pancetta/asparagus/parmesean thing. delicious.

this is a northern italian kind of pancetta--it's smoky, a cousin of speck. it's awesome, of course, because it's bacon!

Thank you, Mikey B., for this little bit of food porn. It has enlivened the evening, and made me hungry to visit the Italian market.

*** Chicken in a Pot, Part II***

It's now 11 pm on the same Saturday night. There was a bat in our bedroom earlier this evening-- another sign of spring? Or perhaps merely a symptom of our own lunacy. We (or, more accurately, H., since I'm terrified of bats) opened the windows. Now the room is cool and fresh.

As I write this, the bat seems to have disappeared into the night sky, and the kitchen is full of dirty dishes. We did indeed make chicken in a pot, and it was perfectly amusing. I followed Bittman's recipe-- for a dish called, quite simply, "chicken in a pot"-- which is characterized by a combination of fresh thyme, leeks, and allspice berries.

The dinner's timing was thrown off somewhat by A.'s continued (albeit waning) nocturnal perambulations, as well as by the uninvited bat. As a result the vegetables were soggier than I would have liked. But the chicken itself remained, as anticipated, fragrant and subtle.

The best part of this dish is is bipartite nature: for the first course, you can serve the broth with oniony butter dumplings that have been steamed in the soup for ten minutes. For the second course, you serve the chicken and vegetables, which have been kept warm in a low oven. Chopped parsley ties the two courses together: folded into the dumplings and sprinkled over the chicken, it brightens both dishes with its powerful herbal presence.

Did the meal communicate the advent of spring? Certainly, the dumplings were fun. But I'll admit that by the time we got around to the chicken, the springlike air of freshness and buoyancy had abandoned us. I'll chalk this up to the lateness of the hour and the events that preceded dinner.

But I'd also like to tinker with this dish. I'd have preferred a lighter-colored, thicker broth-- or at least a lightly-thickened gravy for the chicken course. The leeks and carrots provided a nice flavor, but fewer onions would have rendered the flavor subtler. Perhaps some white wine might have been added. Or even some pancetta.

Amusingly, we did in fact buy some pancetta this evening, which will become part of tomorrow's salad. Did Mikey B. somehow know this, prompting him to send the pornographic image of the pancetta he'd bought? Or is this perhaps the true sign of spring, when everyone runs out for cured pork bellies? Maybe it's not about chicken, after all.

As I sit here with A., with whom I took a brisk constitutional earlier this afternoon, I find my thoughts wandering toward the question of dinner. What to eat tonight. Something to reflect the mood of the season, the mood of the day: not quite spring, but hardly winter.

Like the hardy first shoots of the tulips and daffodils bursting from the ground, a vision appears. I see a chicken. And it's in a pot. The broth is light: delicate and pale in color. There are some vegetables around it.

This should not resemble coq au vin, with its November hues and warmth-inducing richness. Today's chicken— as I now realize— must be a spring chicken. Subtle and light, and fragrant with fresh herbs. It is to be a fulfilled wish: we lift the lid to find brightness and light. The promise of spring.

(To be continued...)

*** A Pornographic Interlude****

It's surely a sign of spring, too, when everyone starts shopping again. This photograph arrives courtesy of Mikey B., who enclosed it in an email this evening. The picture depicts a slab of pancetta, as well as the knife that will shortly render it comestible. The photo, he writes, was (I quote):

It's surely a sign of spring, too, when everyone starts shopping again. This photograph arrives courtesy of Mikey B., who enclosed it in an email this evening. The picture depicts a slab of pancetta, as well as the knife that will shortly render it comestible. The photo, he writes, was (I quote):...taken shortly before it was cubed & fried up for a linguine/pancetta/asparagus/parmesean thing. delicious.

this is a northern italian kind of pancetta--it's smoky, a cousin of speck. it's awesome, of course, because it's bacon!

Thank you, Mikey B., for this little bit of food porn. It has enlivened the evening, and made me hungry to visit the Italian market.

*** Chicken in a Pot, Part II***

It's now 11 pm on the same Saturday night. There was a bat in our bedroom earlier this evening-- another sign of spring? Or perhaps merely a symptom of our own lunacy. We (or, more accurately, H., since I'm terrified of bats) opened the windows. Now the room is cool and fresh.

As I write this, the bat seems to have disappeared into the night sky, and the kitchen is full of dirty dishes. We did indeed make chicken in a pot, and it was perfectly amusing. I followed Bittman's recipe-- for a dish called, quite simply, "chicken in a pot"-- which is characterized by a combination of fresh thyme, leeks, and allspice berries.

The dinner's timing was thrown off somewhat by A.'s continued (albeit waning) nocturnal perambulations, as well as by the uninvited bat. As a result the vegetables were soggier than I would have liked. But the chicken itself remained, as anticipated, fragrant and subtle.

The best part of this dish is is bipartite nature: for the first course, you can serve the broth with oniony butter dumplings that have been steamed in the soup for ten minutes. For the second course, you serve the chicken and vegetables, which have been kept warm in a low oven. Chopped parsley ties the two courses together: folded into the dumplings and sprinkled over the chicken, it brightens both dishes with its powerful herbal presence.

Did the meal communicate the advent of spring? Certainly, the dumplings were fun. But I'll admit that by the time we got around to the chicken, the springlike air of freshness and buoyancy had abandoned us. I'll chalk this up to the lateness of the hour and the events that preceded dinner.

But I'd also like to tinker with this dish. I'd have preferred a lighter-colored, thicker broth-- or at least a lightly-thickened gravy for the chicken course. The leeks and carrots provided a nice flavor, but fewer onions would have rendered the flavor subtler. Perhaps some white wine might have been added. Or even some pancetta.

Amusingly, we did in fact buy some pancetta this evening, which will become part of tomorrow's salad. Did Mikey B. somehow know this, prompting him to send the pornographic image of the pancetta he'd bought? Or is this perhaps the true sign of spring, when everyone runs out for cured pork bellies? Maybe it's not about chicken, after all.

Thursday, March 27, 2008

"A" Vegetables and Free-Range Babies

The dinner would prove prophetic.

Intended as a way to fête H.'s book in advance of the launch party later that evening, our dinner on Saturday was composed almost entirely of "A" vegetables. I hadn't fully worked out the symbolism, but it seemed like an amusing way to give the book high marks. A for Awesome.

We were forced, however, to consume the meal in haste. And thus it became a sign portentous.

I shopped for the dinner with no small degree of glee. Artichokes, Asparagus, Arugula. I considered buying an Aubergine. They all looked sickly, however so I let them lie. The Aubergines reverted back to humble eggplants. Then I switched to fruit: Avocado, Apples, Anjou pears. As I wheeled the cart through the supermarket, I chuckled to myself. How could this go wrong.

A meal of "A" vegetables. I had in mind a salad of arugula, apples, and toasted almonds, with perhaps a bit of avocado on croûtons. Then we would turn to the steamed artichokes, served au naturel, with cruets of drawn butter. The artichokes is a vegetable that somehow signifies victory. Each leaf, dredged scandalously in butter, anticipates the great revelation at the thistle's heart.

As it turns out, we would only manage to unfurl one of our artichokes, with the other relegated to the fridge until long after midnight. Portentous indeed.

After the artichokes, the plan was to become a shade more spartan. We would follow, let's say, with a simple pasta tossed with roasted asparagus, accompanied by fresh bread. The dinner would culminate with poached Anjou pears.

It didn't quite happen that way. We ate the avocado for lunch, and there were no almonds. So the salad included apples and radishes: more of an "Arrrrr" salad than a true "A" vegetable salad. No matter. Who needs purity.

Short on time, and with our babysitter at the door, we roasted the asparagus and ate everything all at once, denuding only the first artichoke and leaving most of the salad unscathed. The pears were abandoned. And so was the second artichoke. We rushed to the party, where there was a great abundance of food.

Strangely, most of the food at the party began with "S." There was sushi; there were shu mai; there was sausage; there were snacks.

It seems that our earlier meal, rushed and compromised as it was, had little to do with the metaphorics of parties, books, or victory. Instead it gave us a hint of what the week to come would offer: Rushing. Compromising. And chasing after A.

On Saturday morning— the day of the meal, and the day of the party– we bought our free-range baby a "big girl" bed. A. had been climbing out of her crib for over a week, dropping to the floor with an enormous thump each time. The thump would inevitably be followed by a protracted wail. This would be followed, in turn, by the sound of parental footsteps rushing to the scene. We always expected the worst.

Luckily, the worst was only this: a thump, a wail, a rush to the scene. And then the spectacle of little A., stark naked, straddling the rail of her crib like a miniature Lady Godiva. Naked and wailing.

We bought her a big-girl bed that day. Ever since then, we've been chasing our free range baby around the house for hours each night. H. spent Sunday and Monday nights working three-hour bedtime shifts on her own, since I had to be out of the house. The past few nights have improved, if only by slow degrees. She climbs into bed with us each morning, touching our faces until we wake up.

Perhaps we should have stuck to "S" vegetables for that fateful Saturday dinner: Sorrel, Spinach, Squash, Seaweed, Salsify, Sunchokes. Anything to invoke sleep, sleep, sleep.

Intended as a way to fête H.'s book in advance of the launch party later that evening, our dinner on Saturday was composed almost entirely of "A" vegetables. I hadn't fully worked out the symbolism, but it seemed like an amusing way to give the book high marks. A for Awesome.

We were forced, however, to consume the meal in haste. And thus it became a sign portentous.

I shopped for the dinner with no small degree of glee. Artichokes, Asparagus, Arugula. I considered buying an Aubergine. They all looked sickly, however so I let them lie. The Aubergines reverted back to humble eggplants. Then I switched to fruit: Avocado, Apples, Anjou pears. As I wheeled the cart through the supermarket, I chuckled to myself. How could this go wrong.

A meal of "A" vegetables. I had in mind a salad of arugula, apples, and toasted almonds, with perhaps a bit of avocado on croûtons. Then we would turn to the steamed artichokes, served au naturel, with cruets of drawn butter. The artichokes is a vegetable that somehow signifies victory. Each leaf, dredged scandalously in butter, anticipates the great revelation at the thistle's heart.

As it turns out, we would only manage to unfurl one of our artichokes, with the other relegated to the fridge until long after midnight. Portentous indeed.

After the artichokes, the plan was to become a shade more spartan. We would follow, let's say, with a simple pasta tossed with roasted asparagus, accompanied by fresh bread. The dinner would culminate with poached Anjou pears.

It didn't quite happen that way. We ate the avocado for lunch, and there were no almonds. So the salad included apples and radishes: more of an "Arrrrr" salad than a true "A" vegetable salad. No matter. Who needs purity.

Short on time, and with our babysitter at the door, we roasted the asparagus and ate everything all at once, denuding only the first artichoke and leaving most of the salad unscathed. The pears were abandoned. And so was the second artichoke. We rushed to the party, where there was a great abundance of food.

Strangely, most of the food at the party began with "S." There was sushi; there were shu mai; there was sausage; there were snacks.

It seems that our earlier meal, rushed and compromised as it was, had little to do with the metaphorics of parties, books, or victory. Instead it gave us a hint of what the week to come would offer: Rushing. Compromising. And chasing after A.

On Saturday morning— the day of the meal, and the day of the party– we bought our free-range baby a "big girl" bed. A. had been climbing out of her crib for over a week, dropping to the floor with an enormous thump each time. The thump would inevitably be followed by a protracted wail. This would be followed, in turn, by the sound of parental footsteps rushing to the scene. We always expected the worst.

Luckily, the worst was only this: a thump, a wail, a rush to the scene. And then the spectacle of little A., stark naked, straddling the rail of her crib like a miniature Lady Godiva. Naked and wailing.

We bought her a big-girl bed that day. Ever since then, we've been chasing our free range baby around the house for hours each night. H. spent Sunday and Monday nights working three-hour bedtime shifts on her own, since I had to be out of the house. The past few nights have improved, if only by slow degrees. She climbs into bed with us each morning, touching our faces until we wake up.

Perhaps we should have stuck to "S" vegetables for that fateful Saturday dinner: Sorrel, Spinach, Squash, Seaweed, Salsify, Sunchokes. Anything to invoke sleep, sleep, sleep.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

What Would It Be?

I call them "sleepover questions." H., among many, finds them infuriating, and in many ways they are. That's why they're relegated to the wee hours of the proverbial sleepover. You know the genre, I'm sure:

"If you won the lottery, how would you spend the money?"

"If you no longer had to work, how would you pass the time?"

"If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?"

As speculative inquiries, such questions purport to solicit deep insights about one's dreams and desires. But they are most often speculative only in form. The answers are, almost without fail, less pressing than the inducement to generate further questions. The game's true pleasure— if you ask me— consists in coming up with the most outlandish question just as everyone else is drifting off to sleep. That way, you never have to answer it yourself.

This post, though preceding sleep only by a matter of minutes, represents a preliminary attempt to resurrect the sleepover question by limiting it to the arena of food. After all, the mode of speculation that animates so much culinary chatter is itself essentially a sleepover question: the notion of the ideal meal. Is there such a thing?

For the sake of keeping the cheesy rhetoric of the late-night conversation alive, I'll put the question this way:

You have been sentenced to death, and you are mandated to request one last meal before your trip to the gallows. Based on some perverse adherence to moral law, you are guaranteed to receive whatever meal you demand, regardless of its rarity or expense. The meal will be made with the best and freshest ingredients and prepared by the top chefs in the land. What would you choose?

It was, I think, Lacenaire who ordered an exquisitely undercooked roast chicken, thus taking delight in consuming what might otherwise have proven fatal in itself.

Would your own choice extend to the otherwise unsanctioned or impossible? Why not a final exploration of taboo: at long last, a chance to discover cannibalism!

Would you choose the baroque route, demanding a banquet so sumptuous as to induce discomfort— or so far-fetched as to involve great nuisance on the behalf of the executioners— or, in the manner of Scheherazade, so prolonged as to stave off the execution itself?

Or would the meal be spartan, purist, nostalgic? A scrambled egg; a slice of cheese pizza; a masterfully-cooked omelet.

Here's where H. usually grows annoyed, and rightly so: having posed the question, I find myself at a loss when it comes to answering it. What makes this question challenging is that it strips dining of all its contextual elements: its environment, its company, its futurity. The hypothetical death-row meal is one you cannot share with anyone. Nor will you have occasion to remember it. The pleasure— provided such a meal could ever be pleasurable— would be limited to the immediacy of the consumption of the food itself. Aesthetics under pressure.

Immediately I find myself imposing conditions rather than menus: if the meal arrived in time to satisfy a great hunger, then it would afford visceral as well as aesthetic satisfaction. Come to think of it, such a precondition seems essential. How meaningful, how ideal, could a last meal possibly be if the penultimate meal— a gruesome trip the the slop-house— were to occur mere minutes beforehand?

Of course, one can start imposing all sorts of other conditions on top of this, death-row circumstances notwithstanding. Ooh, I hope I wouldn't be too cold, or too injured, or too ill, or have stomach cramps. I hope I'd still have the ability to taste and smell. Would the prison cell be too smelly for me to enjoy the meal?

Phooey.

You are mandated a final meal, and you must decide what to order. What would it be? Consider this a survey. I'll post my own answer as soon as I determine what it is.

I'm sure it will come to me as I drift off to sleep.

ADDENDUM: Friday, March 21

H. read last night's blog post and was, as expected, disgruntled. "This is my least favorite post," she said. "I know, I know," I responded, "I posed the question and then refused to answer it."

"There's an unfairness to this," she explained. "You demand that someone else answer first, but offer nothing." H. does, incidentally, use the subjunctive in her daily speech.

But I stand by what I said last night: the answer would, and did, come to me as I drifted off to sleep.

At first I imagined that my death-row meal would be dim sum, the perfect serial meal. How can one not fantasize about the possibility of steam-dish after steam-dish of elaborately prepared dumplings and tit-bits, from tripe and tendon to sticky rice? But I then realized that part of dim sum's pleasure is its appeal to infinity. You can only eat so much on a single visit. But there's always another visit. Such a possibility falls away in the case of a final meal.

As I was drifting off to sleep, it came to me: my death-row meal would be high tea. A testament to my residual Englishness? Though a decision perhaps tainted by the attendant stoicism of the British Empire— we shall face death and refuse to quail!— I realize that high tea affords a near-perfect combination of exquisite preparation, variety of flavor, and, perhaps most importantly, an implicit finitude. It's a tea, after all; not a dinner.

As I was drifting off to sleep, it came to me: my death-row meal would be high tea. A testament to my residual Englishness? Though a decision perhaps tainted by the attendant stoicism of the British Empire— we shall face death and refuse to quail!— I realize that high tea affords a near-perfect combination of exquisite preparation, variety of flavor, and, perhaps most importantly, an implicit finitude. It's a tea, after all; not a dinner.

Lapsang suchong tea, finger sandwiches, pastries, clotted cream, fresh jam, and petits-fours. That's what I'd end with, given that one final choice.

"If you won the lottery, how would you spend the money?"

"If you no longer had to work, how would you pass the time?"

"If you were a tree, what kind of tree would you be?"

As speculative inquiries, such questions purport to solicit deep insights about one's dreams and desires. But they are most often speculative only in form. The answers are, almost without fail, less pressing than the inducement to generate further questions. The game's true pleasure— if you ask me— consists in coming up with the most outlandish question just as everyone else is drifting off to sleep. That way, you never have to answer it yourself.

This post, though preceding sleep only by a matter of minutes, represents a preliminary attempt to resurrect the sleepover question by limiting it to the arena of food. After all, the mode of speculation that animates so much culinary chatter is itself essentially a sleepover question: the notion of the ideal meal. Is there such a thing?

For the sake of keeping the cheesy rhetoric of the late-night conversation alive, I'll put the question this way:

You have been sentenced to death, and you are mandated to request one last meal before your trip to the gallows. Based on some perverse adherence to moral law, you are guaranteed to receive whatever meal you demand, regardless of its rarity or expense. The meal will be made with the best and freshest ingredients and prepared by the top chefs in the land. What would you choose?

It was, I think, Lacenaire who ordered an exquisitely undercooked roast chicken, thus taking delight in consuming what might otherwise have proven fatal in itself.

Would your own choice extend to the otherwise unsanctioned or impossible? Why not a final exploration of taboo: at long last, a chance to discover cannibalism!

Would you choose the baroque route, demanding a banquet so sumptuous as to induce discomfort— or so far-fetched as to involve great nuisance on the behalf of the executioners— or, in the manner of Scheherazade, so prolonged as to stave off the execution itself?

Or would the meal be spartan, purist, nostalgic? A scrambled egg; a slice of cheese pizza; a masterfully-cooked omelet.

Here's where H. usually grows annoyed, and rightly so: having posed the question, I find myself at a loss when it comes to answering it. What makes this question challenging is that it strips dining of all its contextual elements: its environment, its company, its futurity. The hypothetical death-row meal is one you cannot share with anyone. Nor will you have occasion to remember it. The pleasure— provided such a meal could ever be pleasurable— would be limited to the immediacy of the consumption of the food itself. Aesthetics under pressure.

Immediately I find myself imposing conditions rather than menus: if the meal arrived in time to satisfy a great hunger, then it would afford visceral as well as aesthetic satisfaction. Come to think of it, such a precondition seems essential. How meaningful, how ideal, could a last meal possibly be if the penultimate meal— a gruesome trip the the slop-house— were to occur mere minutes beforehand?

Of course, one can start imposing all sorts of other conditions on top of this, death-row circumstances notwithstanding. Ooh, I hope I wouldn't be too cold, or too injured, or too ill, or have stomach cramps. I hope I'd still have the ability to taste and smell. Would the prison cell be too smelly for me to enjoy the meal?

Phooey.

You are mandated a final meal, and you must decide what to order. What would it be? Consider this a survey. I'll post my own answer as soon as I determine what it is.

I'm sure it will come to me as I drift off to sleep.

ADDENDUM: Friday, March 21

H. read last night's blog post and was, as expected, disgruntled. "This is my least favorite post," she said. "I know, I know," I responded, "I posed the question and then refused to answer it."

"There's an unfairness to this," she explained. "You demand that someone else answer first, but offer nothing." H. does, incidentally, use the subjunctive in her daily speech.

But I stand by what I said last night: the answer would, and did, come to me as I drifted off to sleep.

At first I imagined that my death-row meal would be dim sum, the perfect serial meal. How can one not fantasize about the possibility of steam-dish after steam-dish of elaborately prepared dumplings and tit-bits, from tripe and tendon to sticky rice? But I then realized that part of dim sum's pleasure is its appeal to infinity. You can only eat so much on a single visit. But there's always another visit. Such a possibility falls away in the case of a final meal.

As I was drifting off to sleep, it came to me: my death-row meal would be high tea. A testament to my residual Englishness? Though a decision perhaps tainted by the attendant stoicism of the British Empire— we shall face death and refuse to quail!— I realize that high tea affords a near-perfect combination of exquisite preparation, variety of flavor, and, perhaps most importantly, an implicit finitude. It's a tea, after all; not a dinner.

As I was drifting off to sleep, it came to me: my death-row meal would be high tea. A testament to my residual Englishness? Though a decision perhaps tainted by the attendant stoicism of the British Empire— we shall face death and refuse to quail!— I realize that high tea affords a near-perfect combination of exquisite preparation, variety of flavor, and, perhaps most importantly, an implicit finitude. It's a tea, after all; not a dinner.Lapsang suchong tea, finger sandwiches, pastries, clotted cream, fresh jam, and petits-fours. That's what I'd end with, given that one final choice.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

Coins of the Realm: A Confessional

When it comes to food, and especially to dining out, the term "embarrassment of riches" takes on distinctive physical properties. You get fat. You feel bloated, conspicuous, profligate. There are biological consequences to a surfeit of fine dining: the hiatal hernia acts up; the metabolism grinds to a halt; the back pains increase their intensity.

When it comes to food, and especially to dining out, the term "embarrassment of riches" takes on distinctive physical properties. You get fat. You feel bloated, conspicuous, profligate. There are biological consequences to a surfeit of fine dining: the hiatal hernia acts up; the metabolism grinds to a halt; the back pains increase their intensity.Such are the effects of the past five days. I'm glorying in them. Such marvels! But oh, such consequences.

There's little else to do than offer a litany of my earthly delights. Thus, with an added mea culpa for this double indulgence: On Thursday, hot thin-crust pizza in New York with S.W., G., and baby Neko). On Friday, a massive corned beef and tongue sandwich at Nana's deli in Livingston, NJ. That was lunch. For dinner, a lovely carne asada at Lolita's in Philly.

I'll stop for a breath here. The dinner at Lolita's began with a tamale made with huitalacoche, one of my favorite edible corn fungi. The meal ended with a prickly-pear flavored crème brulée, bright fuschia in color. This was only the start of things. Lunch the next day was at Sazon at 10th and Spring Garden, a friendly Venezuelan restaurant H. and I visited with J., G., and her brother Felipe. They're regulars. Arepas and café con leche were the stars of the hour. And speaking of hours, it was but a scant hour or so later that we met up for drinks and oysters with our friend J. at a remarkably faithful rendition of a French brasserie at 5th and Bainbridge called Coquette. First oysters of the year. And what a revelation: the oysters were served with a shallot vinaigrette that complemented their freshness perfectly. But it didn't end there.

Soon after that we headed to M. and E.'s place around the corner. It was M's 40th birthday, and we'd soon be heading to a party in his honor. But when we arrived at their apartment, we faced a spread of delices from Claudio's market: hot ham, soprasetta, a pair of fine cheeses, a selection of herrings and olives, and several loaves of Sarcone's bread. And then there was the ham. Imagine a fine, light pink ham with a flavor so paradoxical that it might only be described as aggressively delicate. The story goes that when E. first tasted the ham, she cried out, "Dear God, what animal is this ham made from? Unicorns?" E., it should be said, is a poet.

Any litany that has gone on so long as to include unicorns is surely reaching its conclusion, but this one isn't over yet. The party was catered, and the hors-d'oeuvre were themselves remarkable. This was, however, the sole occasion throughout the long weekend that I didn't embarrass myself through gluttony— but I can explain. My gluttony of food was, on this occasion, trumped by my gluttony for books. The party, you see, took place at a bookstore. And the bookstore (Brickbat Books, on 4th and Bainbridge) is owned by PR-G. PR-G's taste in books makes me weak in the knees, so I spent much of the party piling up books to bring home with me. Of course, one can never truly attend a party without a bit of late-night grazing as a nightcap. So when we returned to M. and E.'s apartment that night, I polished off the remainder of the unicorn ham. Please don't judge me.

Sunday might seem to have promised a reasonable return to asceticism, as we spent much of the day driving. But we drove rapidly, breathlessly, back to central PA in time to attend a brunch at our dear colleague J's house. After a bracing pitcher of Bloody Marys, we tucked into a vegetable quiche that beckoned us to welcome in spring; this was complemented by a host of bagels, cream cheese, and smoked salmon. We meandered home well beyond A's bedtime, feeling vague yet content.

This brings us, at last, to yesterday. Yesterday was St. Patrick's, and dear St. Patrick (P1) had us all over to his chateau for corned beef and cabbage. St. Paddy corned the beef himself, and it was a revelation. The beef, and the cabbage, carrots, and potatoes that accompanied it, were perfumed with cloves. No boiled dinner has ever come close to this: normally, "boiled dinner" tastes about as subtle as it sounds. This, of course, is part of its pleasure. But St. Paddy elevated the dish to saintly new heights.

I'm surely going to hell.

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Best Part of the Cow?

It may not be in especially good taste to suggest a body-parts contest for cattle. All the same, I've long fancied the aesthetics of the beef chart (and shall thus, in the same breath, recommend Stanley Lobel's classic The Complete Book of Meat). So why not launch a hypothetical contest, at least: what's the best part of the cow?

It may not be in especially good taste to suggest a body-parts contest for cattle. All the same, I've long fancied the aesthetics of the beef chart (and shall thus, in the same breath, recommend Stanley Lobel's classic The Complete Book of Meat). So why not launch a hypothetical contest, at least: what's the best part of the cow?I think one's choice of beef cuts reveals much about one's preference as a cook. My uncle, for instance, makes a jaw-droppingly terrific jellied tongue. It may very well be the best thing I've ever eaten, full stop. (N.B.: we'll be visiting him this May, so perhaps he can be convinced to make it again). The recipe, like my uncle, is time-consuming and elaborate, but well worth the wait.

Were it possible to induce all the meat-eaters I know to cast lots for their favorite cut of beef, how would the spoils be divided? Who would sprint for the tenderloin, and who would scramble to get their hands on the liver, or the sweetbreads, or the tripe? The game would prove revealing, I'm sure.

Incidentally, our neighbors M. and J. recently purchased a quarter cow from a local farm. One hundred and thirty one pounds of frozen beef. They've got the whole thing on ice in their basement. Or rather, in their freezer lies a quarter-cow's worth of choice cuts; most of it is ground chuck. They didn't have to race to claim their share of my imaginary cow: they bought up the lion's share. That's one way around the problem.

My own interest— at least this week— has settled on the humble oxtail.

This choice, dare I say, says a lot about me. First, I'm cheap. Oxtails are often sold as soup bones— like shanks, but with more cartilage.

This choice, dare I say, says a lot about me. First, I'm cheap. Oxtails are often sold as soup bones— like shanks, but with more cartilage.Second, I like braising meat, since this appeals to my aesthetic as a cook: the longer a dish cooks, the farther in advance it can be prepared, and thus the more time there is to socialize with dinner guests. And oxtails are a braising meat par excellence. In fact, there's little else you can do with them.

Nothing makes a better ragout than oxtails. They're composed almost entirely of cartilage. So the same unguent richness that makes them a fine soup base makes them an even better ragout. Over time, the cartilage breaks down, which both flavors and thickens the ragout.

Here's the dish we made last night; the recipe is adapted from Marcella Hazan:

In a heavy pot or dutch oven, sweat two small chopped onions, three chopped carrots, and 3 cloves garlic in some olive oil. Meanwhile, brown 3 pounds of prepared oxtails in some olive oil. When the oxtails are browned all over, place them in the dutch oven amongst the vegetables. Deglaze both pans with a healthy amount of dry white wine-- about 2 cups-- and pour everything into the dutch oven. Add a can of plum tomatoes, chopped, along with a healthy grind of black pepper. Simmer, mostly covered, for 1 1/2 hours, turning the meat occasionally. If the braising liquid gets too dry, add a cup or so of water.

After the oxtails have been simmering for 1 1/2 hours, add 3-4 stalks of celery, coarsely chopped. This gives the dish a crucial brightness (and prevents it from developing the same lugubrious stew flavor to which so many braised meat dishes are prone). Simmer for another 45 minutes. When the meat is falling off the bone, remove the oxtails, cool slightly, and pull off the meat. Return the meat to the pot and discard the bones.

In a pot of salted, boiling water, cook a box of pasta (penne rigate, for instance) until it's al dente; drain, and add the pasta to the ragout. Simmer for a few minutes, check for seasoning, and serve.

Sunday, March 9, 2008

A.O.C. in the U.S.A.?

Last night H. and I shared a bottle (the shorty kind: 375 ml) of Banyuls dessert wine. I still have the empty bottle in front of me. For future reference, it's a Domaine du Mas Blanc, Rimage 2004. Banyuls is one of the rare red dessert wines-- with the notable exception, of course, of port. We're forever on the lookout for it, ever since our friends B. and L. introduced us to it a number of years ago.

So I was delighted to happen across a bottle while playing hooky from a conference this weekend in Washington DC. I brought the bottle home with me. It took something of a miracle not to have drunk it on the spot.

Incidentally, I also had great sushi while in DC. But more on that some other time.

Banyuls, in addition to being a delicious dessert wine, is also a geographical region. That's the whole point of the "AOC" denomination, of course: the French appellation d'origine controllée (like the Italian Denominazione di origine controllata, the Spanish Denominación de Origen, and so forth) demarcates regionally-specific products whose standards of quality are protected by a national institution. This is not, however, simply a administrative organ for maintaining quality control, such as the USDA. For it is also a system of regional support and specialization. Thus, for instance, if you want to find out more about the Banyuls region, you can go to the Banyuls web site: www.banyuls.com

Short of exercising some misty-eyed Europhilia, I wonder if there's a way to develop a system like this in the US. To a certain extent it already exists. There are, for instance, a number of US wine regions, as legislated by some tax-based department of tobacco and alcohol. But the very fact that this bureaucracy derives from taxation already makes me suspicious. Especially given the lingering traces of the Prohibition movement in the way states determine their blue laws. What about a broader sense of regionalism, devoted as much to food as to wine?

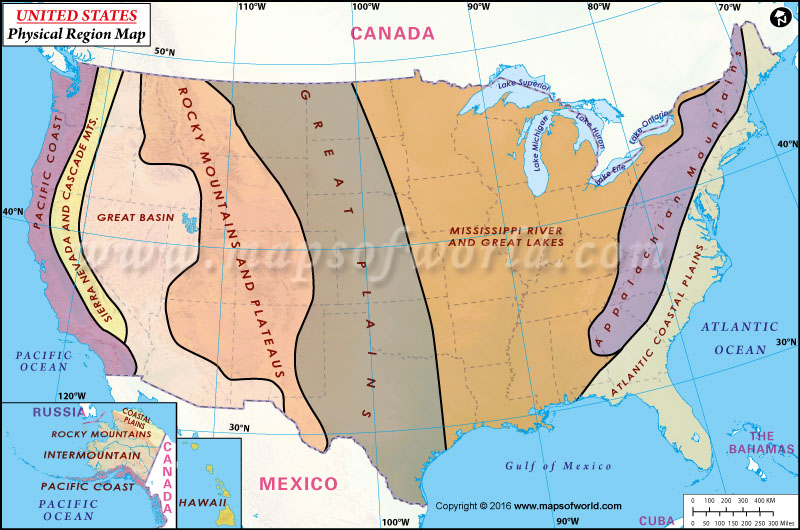

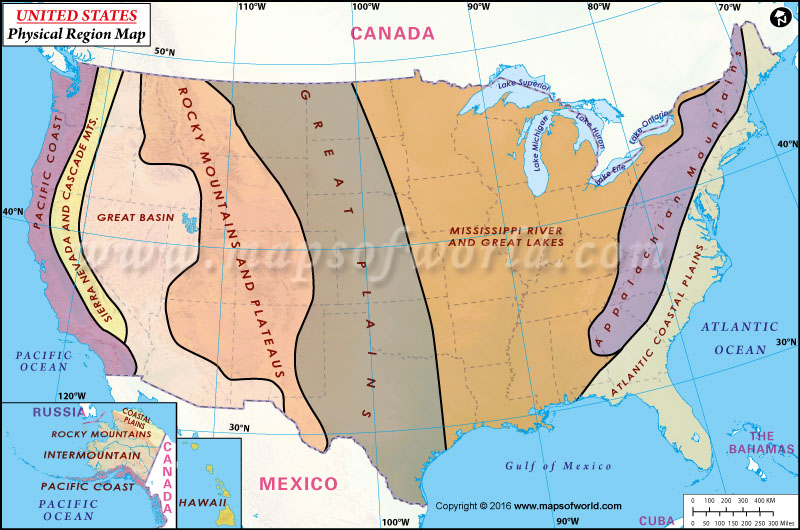

Let's side-step the problem of administration for the moment. It strikes me that a system for regional specificity in the US would first have to come up with a sense of how the country breaks down on regional lines. No easy task. Where would we start? Would the regions be derived from the products, or the products from the regions?

For one, not every region bears the same set of products. New England clam chowder has a cream base. Manhattan clam chowder has a tomato base. Rhode Island clam chowder (also native to parts of Connecticut) has a clear broth base. Aha! A regionalism! Indeed, there is no Minnesota clam chowder, since they don't have clams. San Francisco has clams, but do they don't have a native chowder.

Alternatively, some artisinal products are themselves regionally specific: scrapple, as far as I know, is limited to the Amish and Mennonite regions of central Pennsylvania and Ohio. Steam beer is a San Francisco product.

What might a regional map of the US look like? Cruising around the internet yields numerous attempts to derive some sort of overall coherence, from the silly—

— to the drily bureaucratic

But does a region have to conform to the outlines of a state? According to the Alcohol and Tax and Trade Bureau web site, an appellation of origin can be as small as three counties (although it then becomes a "multi-county" appellation). Lines of political demarcation might have something to do with US regionalism-- the Mason-Dixon line comes to mind here-- but I can't imagine that they're so significant as to determine the contours of every region.

Another possibility might be to use the USDA climate-zone map as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.

as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.

We're not raised to think this way. Think of your grade-school social science classes: it's all based on economics and raw materials, not on artisanal products made with these raw materials. Idaho= potato. California and Florida= oranges. But what do local folks make with them?

I'll come back to this idea from time to time, as it's both a concern and an interest of mine. I also welcome any thoughts.

So I was delighted to happen across a bottle while playing hooky from a conference this weekend in Washington DC. I brought the bottle home with me. It took something of a miracle not to have drunk it on the spot.

Incidentally, I also had great sushi while in DC. But more on that some other time.

Banyuls, in addition to being a delicious dessert wine, is also a geographical region. That's the whole point of the "AOC" denomination, of course: the French appellation d'origine controllée (like the Italian Denominazione di origine controllata, the Spanish Denominación de Origen, and so forth) demarcates regionally-specific products whose standards of quality are protected by a national institution. This is not, however, simply a administrative organ for maintaining quality control, such as the USDA. For it is also a system of regional support and specialization. Thus, for instance, if you want to find out more about the Banyuls region, you can go to the Banyuls web site: www.banyuls.com

Short of exercising some misty-eyed Europhilia, I wonder if there's a way to develop a system like this in the US. To a certain extent it already exists. There are, for instance, a number of US wine regions, as legislated by some tax-based department of tobacco and alcohol. But the very fact that this bureaucracy derives from taxation already makes me suspicious. Especially given the lingering traces of the Prohibition movement in the way states determine their blue laws. What about a broader sense of regionalism, devoted as much to food as to wine?

Let's side-step the problem of administration for the moment. It strikes me that a system for regional specificity in the US would first have to come up with a sense of how the country breaks down on regional lines. No easy task. Where would we start? Would the regions be derived from the products, or the products from the regions?

For one, not every region bears the same set of products. New England clam chowder has a cream base. Manhattan clam chowder has a tomato base. Rhode Island clam chowder (also native to parts of Connecticut) has a clear broth base. Aha! A regionalism! Indeed, there is no Minnesota clam chowder, since they don't have clams. San Francisco has clams, but do they don't have a native chowder.

Alternatively, some artisinal products are themselves regionally specific: scrapple, as far as I know, is limited to the Amish and Mennonite regions of central Pennsylvania and Ohio. Steam beer is a San Francisco product.

What might a regional map of the US look like? Cruising around the internet yields numerous attempts to derive some sort of overall coherence, from the silly—

— to the drily bureaucratic

But does a region have to conform to the outlines of a state? According to the Alcohol and Tax and Trade Bureau web site, an appellation of origin can be as small as three counties (although it then becomes a "multi-county" appellation). Lines of political demarcation might have something to do with US regionalism-- the Mason-Dixon line comes to mind here-- but I can't imagine that they're so significant as to determine the contours of every region.

Another possibility might be to use the USDA climate-zone map

as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.

as a model for regions that gain their specificity from temperature fluctuation. It's a starting-point, at least. After all, this map helps determine what kinds of plants can be grown in various parts of the country. It might be a helpful way to think about what kinds of produce, and thus also of regional food products, come from various parts of the country.We're not raised to think this way. Think of your grade-school social science classes: it's all based on economics and raw materials, not on artisanal products made with these raw materials. Idaho= potato. California and Florida= oranges. But what do local folks make with them?

I'll come back to this idea from time to time, as it's both a concern and an interest of mine. I also welcome any thoughts.

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

Blade!

I'm procrastinating: I should be working. I've got an essay to write, and, whether through alchemy or incantation, that essay must find a way to complete itself by Friday. I'm placing my bet on incantation; alchemy demands too much work. Better just to shout out a few words and wait for the puff of smoke.

So I'm not writing that essay. Instead, I'm using the time to reflect on why I chose this career in the first place, rather than, say, working in a kitchen. I harbor no illusions that I might have been happy, or successful, as a cook. Rather, as I mentioned in a post the other week, it's because I spent just enough time working as a line cook to develop a complex about it.

Why do we work? We sell our time, our labor, our youth, in order to put food on the table and a roof over our heads. Right? Yes, but the more successful we get, the more we allow ourselves to forget these basic reasons. We psychologize; we aestheticize. We love our jobs because they make us feel smart. Or rich. Or loved. Or important. Or like we're saving the world. Or at the very least, they give us something to grumble about. This is how we enter the happy bourgeoisie.

Working as a line cook brings the equation back to its essentials: there is little illusion that what you do when you work in a kitchen is anything other than selling your labor. The work pays for the roof, the food, and for the margin of excess beyond that. This usually means booze.

I'm not getting all Marxist here. On the whole, kitchen labor is hardly proletarian, despite what George Orwell suggests in Down and Out in Paris and London. In return for working in a kitchen— and this why I have a complex about it— you get a little share of what it is you're helping to make. I don't mean the food, or the profits, or anything quite so literal. Rather, what you get is an experience of the restaurant-machine itself— the line— in which you play a part. You're a grunt, but not a cog. Your peculiarities play a part in the machine, and the machine adapts itself to you, just as you're forced to adapt to it. This is a pretty wild ride, as tiring and as short-lived as it may be.

To be more specific: when you work on a line, your personality falls away in a flash as soon as there's a rush of orders. Once you get slammed with orders, you're nobody. And if you can't keep up the pace, you're replaceable. But the difference from any true assembly-line is that this pace isn't constant. As soon as the pace shifts, the whole workplace changes. Before the rush, there's one system: preparing, chopping, stocking, and the like. It's like a band tuning up for a performance. Here, personality and peculiarity are tolerated in moderation, provided that they're an accompaniment to work. After the rush there's an entirely different system. When all that remains is to clean, to break things down, to regroup: this is when personality rears its head again, and opens its lungs.

This lifestyle of varying speeds works like a drug. The other elements of your life recede and fade in importance. What looms instead are the immediacies of the evening ahead: the impending rush, and the impending release. What might otherwise be mere embellishments take on supreme importance: banter, gossip, harsh words, pranks. This forms the fabric of experience, turning your thoughts back to the immanence of work. You go home afterward, but for what? To rest up for another day. To drink off the stress. To pay bills.

There is no question like "do I really love my job?" No; you hate the job. It steals your life. But it owns you, it possesses you, and you live for it. This is a wonderful way to spend a summer, or a few romantic years. It's a tough way to grind out a living.

There was a loud-mouthed, slop-bellied chef at Tonya's Roadhouse who was my hero. His name was Jim, but everyone else required a new, better name than the ones they had. My nickname was derived all too conveniently from my surname: Burn! A swell tag for a greenhorn fry cook.

"Burn! Drop another Fristo!" You get the idea. Jim was the perfect kitchen organism: he was well-trained and could more or less sleepwalk through an evening of baked scrod and prime-rib dinners. The rest of the time he was as high as a kite. Some people can handle the cycle of addiction. As a result, Jim's adaptation to the diurnal rhythm of kitchen work allowed his mind, and his mouth, to roam freely throughout the evening. He played air guitar, he played jokes, he befriended all the waitstaff. In his spare time he showed me how things worked.

My friend Todd, who joined the staff as a dishwasher during my second summer at Tonya's, never graduated from the dishwasher station. It was awkward; I could see him to my left as I worked on the line, observing him at work from my position of relative privilege. Jim had trouble nicknaming him.

One day, though, Todd either cut himself with a chef's knife, or— my memory's a bit cloudy here— was perhaps talking about knives. Todd had an extensive collection of sharp things: butterfly knives, throwing stars, and various other flea-market ninja gear. So perhaps he was talking about knives. From this moment on he became "Blade."

Now, whereas the cry of "Burn" was uniformly followed by a set of instructions or a list of orders, a dishwasher is a dishwasher. There's neither need nor profit in instructing a dishwasher to do anything; he simply does his job. So Jim would simply yell out Todd's nickname at random. "Blade!" he'd should when Todd arrived at work. And whenever the rush of orders risked becoming overwhelming, or whenever tempers started to mount, Jim would simply should out "Blade!" at the top of his lungs.

Todd loved this. He started calling himself Blade during our off-work hours. He even said it with Jim's special inflection. This might sound silly, but it's part of the drug.

So I'm not writing that essay. Instead, I'm using the time to reflect on why I chose this career in the first place, rather than, say, working in a kitchen. I harbor no illusions that I might have been happy, or successful, as a cook. Rather, as I mentioned in a post the other week, it's because I spent just enough time working as a line cook to develop a complex about it.

Why do we work? We sell our time, our labor, our youth, in order to put food on the table and a roof over our heads. Right? Yes, but the more successful we get, the more we allow ourselves to forget these basic reasons. We psychologize; we aestheticize. We love our jobs because they make us feel smart. Or rich. Or loved. Or important. Or like we're saving the world. Or at the very least, they give us something to grumble about. This is how we enter the happy bourgeoisie.

Working as a line cook brings the equation back to its essentials: there is little illusion that what you do when you work in a kitchen is anything other than selling your labor. The work pays for the roof, the food, and for the margin of excess beyond that. This usually means booze.

I'm not getting all Marxist here. On the whole, kitchen labor is hardly proletarian, despite what George Orwell suggests in Down and Out in Paris and London. In return for working in a kitchen— and this why I have a complex about it— you get a little share of what it is you're helping to make. I don't mean the food, or the profits, or anything quite so literal. Rather, what you get is an experience of the restaurant-machine itself— the line— in which you play a part. You're a grunt, but not a cog. Your peculiarities play a part in the machine, and the machine adapts itself to you, just as you're forced to adapt to it. This is a pretty wild ride, as tiring and as short-lived as it may be.

To be more specific: when you work on a line, your personality falls away in a flash as soon as there's a rush of orders. Once you get slammed with orders, you're nobody. And if you can't keep up the pace, you're replaceable. But the difference from any true assembly-line is that this pace isn't constant. As soon as the pace shifts, the whole workplace changes. Before the rush, there's one system: preparing, chopping, stocking, and the like. It's like a band tuning up for a performance. Here, personality and peculiarity are tolerated in moderation, provided that they're an accompaniment to work. After the rush there's an entirely different system. When all that remains is to clean, to break things down, to regroup: this is when personality rears its head again, and opens its lungs.

This lifestyle of varying speeds works like a drug. The other elements of your life recede and fade in importance. What looms instead are the immediacies of the evening ahead: the impending rush, and the impending release. What might otherwise be mere embellishments take on supreme importance: banter, gossip, harsh words, pranks. This forms the fabric of experience, turning your thoughts back to the immanence of work. You go home afterward, but for what? To rest up for another day. To drink off the stress. To pay bills.

There is no question like "do I really love my job?" No; you hate the job. It steals your life. But it owns you, it possesses you, and you live for it. This is a wonderful way to spend a summer, or a few romantic years. It's a tough way to grind out a living.

There was a loud-mouthed, slop-bellied chef at Tonya's Roadhouse who was my hero. His name was Jim, but everyone else required a new, better name than the ones they had. My nickname was derived all too conveniently from my surname: Burn! A swell tag for a greenhorn fry cook.

"Burn! Drop another Fristo!" You get the idea. Jim was the perfect kitchen organism: he was well-trained and could more or less sleepwalk through an evening of baked scrod and prime-rib dinners. The rest of the time he was as high as a kite. Some people can handle the cycle of addiction. As a result, Jim's adaptation to the diurnal rhythm of kitchen work allowed his mind, and his mouth, to roam freely throughout the evening. He played air guitar, he played jokes, he befriended all the waitstaff. In his spare time he showed me how things worked.

My friend Todd, who joined the staff as a dishwasher during my second summer at Tonya's, never graduated from the dishwasher station. It was awkward; I could see him to my left as I worked on the line, observing him at work from my position of relative privilege. Jim had trouble nicknaming him.

One day, though, Todd either cut himself with a chef's knife, or— my memory's a bit cloudy here— was perhaps talking about knives. Todd had an extensive collection of sharp things: butterfly knives, throwing stars, and various other flea-market ninja gear. So perhaps he was talking about knives. From this moment on he became "Blade."

Now, whereas the cry of "Burn" was uniformly followed by a set of instructions or a list of orders, a dishwasher is a dishwasher. There's neither need nor profit in instructing a dishwasher to do anything; he simply does his job. So Jim would simply yell out Todd's nickname at random. "Blade!" he'd should when Todd arrived at work. And whenever the rush of orders risked becoming overwhelming, or whenever tempers started to mount, Jim would simply should out "Blade!" at the top of his lungs.

Todd loved this. He started calling himself Blade during our off-work hours. He even said it with Jim's special inflection. This might sound silly, but it's part of the drug.

Monday, March 3, 2008

Fresh and Clean

The New Yorker recently published a lovely personal essay on nicknames by a fellow named David Owen. At once a memoir and a meditation, the article was a perfect February read. It was breezy and yet tightly crafted; and whereas it did contain a number of poignant moments, the essay scrupulously avoided melodrama, instead remaining defiantly light-hearted.

There's little place for such subtlety on this humble blog. Around here it's all cutlass-waving and damp handkerchiefs. All the same, it's hard to pass up a chance to talk about nicknames, given that the compulsion to rebaptize seems especially acute in the field of cookery.

We all know how judgments of taste can quickly turn into epithets. "Greasy spoon" fondly delineates a whole genre of classic diners. The appeal of working at a greasy spoon is that one can aspire to become a hash-slinger. On the less generous side, there's a street in the 5th arrondissement in Paris known to tour books as "bacteria alley." Analogously, yet no less unfairly, my father referred to the tin-clad snack trucks that came to the factory as "roach coaches."

Fast-food restaurants often find a special place in a family's basic idiom. In their capacity as surrogate nannies or cooks, they're recast as intimates. Unsurprisingly, McDonald's yields a host of polynyms and epithets, from the inocuous "Mickey D's" and the (often-ironic) "Golden Arches," to the imitative cry of "MaDonnads!" we remember from Eddie Murphy's stand-up days. In France, it's "MacDo"; in Germany, I am told, it's "McDoof."

And that's only one fast-food chain. Try listening to a Spanish-language radio station and not suddenly having the desire to go to "Burrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrger King."

Far more interesting, though, are the nicknames people give to food itself. A large number of them are nauseatingly cute; the British are masters in this category. "Bubble and squeak" is the English term for a mash of leftover potatoes and vegetables; in Scotland it's the ever more precious "Rumbletethumps." Like the game of mumbletypeg, this dish couldn't sound any more homespun. Both have disarmingly cutesy names, although the latter is far more dangerous.

My dear cousin grew up referring to boiled eggs as "noddies." My aunt would draw little faces on the eggs, and set them in little porcelain egg-cups. Then my young cousin would crack the egg with a spoon and cut off the top, first lobotomizing the poor thing and then scooping out its middle. Upon reflection, perhaps "noddy" wasn't a nickname at all, but instead a euphemism for the egg's unnatural fate– just as putting an animal to sleep means that it won't be greeting you at the door when you return home.

The crasser food nicknames tend to fall to the US military: given that soldiers dine in mess halls and that the food is cooked by "slop jockeys," this is hardly a surprise. Calling hot dogs "tube steaks" has always made me chuckle. More cringeworthy are the names for creamed chipped beef on toast, known most famously as "shit on a shingle." This is infinitely preferable, though, to the other name I once heard for it, which was "Skinned Injun." No joke.

Not all food nicknames, incidentally, are brief. At our favorite Vietnamese restaurant in Philadelphia, the Vietnam Palace ("The Palace") on 11th and Race, H. would order her favorite soup by means of its description. There was a children's soup they'd serve off-menu, which consisted of a clear chicken broth with noodles, greens, and steamed chicken. It was, in other words, chicken noodle soup.

A miraculous cold remedy and general spirit-raiser, this soup was notable as well for its clean, fresh flavors. So this is how H. would order it. "I will have," she would ask, with an eager pause, "that clean, fresh soup. You know, the one that's fresh and clean." The waiters always knew what to bring.

There's little place for such subtlety on this humble blog. Around here it's all cutlass-waving and damp handkerchiefs. All the same, it's hard to pass up a chance to talk about nicknames, given that the compulsion to rebaptize seems especially acute in the field of cookery.

We all know how judgments of taste can quickly turn into epithets. "Greasy spoon" fondly delineates a whole genre of classic diners. The appeal of working at a greasy spoon is that one can aspire to become a hash-slinger. On the less generous side, there's a street in the 5th arrondissement in Paris known to tour books as "bacteria alley." Analogously, yet no less unfairly, my father referred to the tin-clad snack trucks that came to the factory as "roach coaches."

Fast-food restaurants often find a special place in a family's basic idiom. In their capacity as surrogate nannies or cooks, they're recast as intimates. Unsurprisingly, McDonald's yields a host of polynyms and epithets, from the inocuous "Mickey D's" and the (often-ironic) "Golden Arches," to the imitative cry of "MaDonnads!" we remember from Eddie Murphy's stand-up days. In France, it's "MacDo"; in Germany, I am told, it's "McDoof."

And that's only one fast-food chain. Try listening to a Spanish-language radio station and not suddenly having the desire to go to "Burrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrger King."

Far more interesting, though, are the nicknames people give to food itself. A large number of them are nauseatingly cute; the British are masters in this category. "Bubble and squeak" is the English term for a mash of leftover potatoes and vegetables; in Scotland it's the ever more precious "Rumbletethumps." Like the game of mumbletypeg, this dish couldn't sound any more homespun. Both have disarmingly cutesy names, although the latter is far more dangerous.

My dear cousin grew up referring to boiled eggs as "noddies." My aunt would draw little faces on the eggs, and set them in little porcelain egg-cups. Then my young cousin would crack the egg with a spoon and cut off the top, first lobotomizing the poor thing and then scooping out its middle. Upon reflection, perhaps "noddy" wasn't a nickname at all, but instead a euphemism for the egg's unnatural fate– just as putting an animal to sleep means that it won't be greeting you at the door when you return home.

The crasser food nicknames tend to fall to the US military: given that soldiers dine in mess halls and that the food is cooked by "slop jockeys," this is hardly a surprise. Calling hot dogs "tube steaks" has always made me chuckle. More cringeworthy are the names for creamed chipped beef on toast, known most famously as "shit on a shingle." This is infinitely preferable, though, to the other name I once heard for it, which was "Skinned Injun." No joke.

Not all food nicknames, incidentally, are brief. At our favorite Vietnamese restaurant in Philadelphia, the Vietnam Palace ("The Palace") on 11th and Race, H. would order her favorite soup by means of its description. There was a children's soup they'd serve off-menu, which consisted of a clear chicken broth with noodles, greens, and steamed chicken. It was, in other words, chicken noodle soup.

A miraculous cold remedy and general spirit-raiser, this soup was notable as well for its clean, fresh flavors. So this is how H. would order it. "I will have," she would ask, with an eager pause, "that clean, fresh soup. You know, the one that's fresh and clean." The waiters always knew what to bring.

Sunday, March 2, 2008

What's Going to Happen

Here is what will happen this week. Foodwise, that is. (Other predictions might be a shade more risky: a surprise stock-market surge? A Hillary comeback? I've no business getting involved in any such prophecies). But here are three virtual certainties:

First, I'm going to try my hand at making gnocci. I've been inspired by A.N.'s words about the difficulty of the venture, as well as by my own recollections of gummy, heavy dumplings. According to Marcella Hazan, whose recipes I enjoy but who knows no fear of mystification, the key to success is the potato itself. One must use "boiling" potatoes, rather than the more waxy salad potatoes or the starchy Idaho baking potatoes. It just so happens that the two-for-one bagged potato sale some weeks ago concerned the anonymous boiling variety. So we might be in luck.

Second, it's been a long time since we've had pumpkin and bacon risotto. So why not this week? One of the peculiarities of this dish is that I refuse to call it what it actually is. There's no pumpkin involved. It's really a squash and bacon risotto. But this sounds less profound, somehow. Calling it pumpkin adds an element of mystery, and perhaps a hint of the regional, the teroir: can you really get hold of a tasty pie pumpkin with as much flavor as a winter squash? No. But it's fun to pretend.

Third, H. recently forwarded me a Bittman recipe for a fish stew with fennel and Pernod. In other words, it's a Bouillabaisse. But a simplified, middle-of the week version. I've toyed with a number of similar recipes, so this should be quite familiar. More importantly, it's delicious-- and thus a savory means for riding out the last leg of Winter's tortuous journey. We can dream of warm Mediterranean air and al fresco dining.

You know the scene already: the table overlooking the bay. The sun-bleached seaside architecture rising up against a background of deep Mediter- ranean blue. The bottle of crisp, dry white wine at the table The smells of lavender, salt air, and anisette. Straight out of a travel brochure. (Literally, in this case. Welcome to Monaco).

Whatever it takes to survive the last few weeks of winter in central Pennsylvania. Who cares if it's someone else's fantasy!

First, I'm going to try my hand at making gnocci. I've been inspired by A.N.'s words about the difficulty of the venture, as well as by my own recollections of gummy, heavy dumplings. According to Marcella Hazan, whose recipes I enjoy but who knows no fear of mystification, the key to success is the potato itself. One must use "boiling" potatoes, rather than the more waxy salad potatoes or the starchy Idaho baking potatoes. It just so happens that the two-for-one bagged potato sale some weeks ago concerned the anonymous boiling variety. So we might be in luck.

Second, it's been a long time since we've had pumpkin and bacon risotto. So why not this week? One of the peculiarities of this dish is that I refuse to call it what it actually is. There's no pumpkin involved. It's really a squash and bacon risotto. But this sounds less profound, somehow. Calling it pumpkin adds an element of mystery, and perhaps a hint of the regional, the teroir: can you really get hold of a tasty pie pumpkin with as much flavor as a winter squash? No. But it's fun to pretend.

Third, H. recently forwarded me a Bittman recipe for a fish stew with fennel and Pernod. In other words, it's a Bouillabaisse. But a simplified, middle-of the week version. I've toyed with a number of similar recipes, so this should be quite familiar. More importantly, it's delicious-- and thus a savory means for riding out the last leg of Winter's tortuous journey. We can dream of warm Mediterranean air and al fresco dining.

You know the scene already: the table overlooking the bay. The sun-bleached seaside architecture rising up against a background of deep Mediter- ranean blue. The bottle of crisp, dry white wine at the table The smells of lavender, salt air, and anisette. Straight out of a travel brochure. (Literally, in this case. Welcome to Monaco).

Whatever it takes to survive the last few weeks of winter in central Pennsylvania. Who cares if it's someone else's fantasy!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)